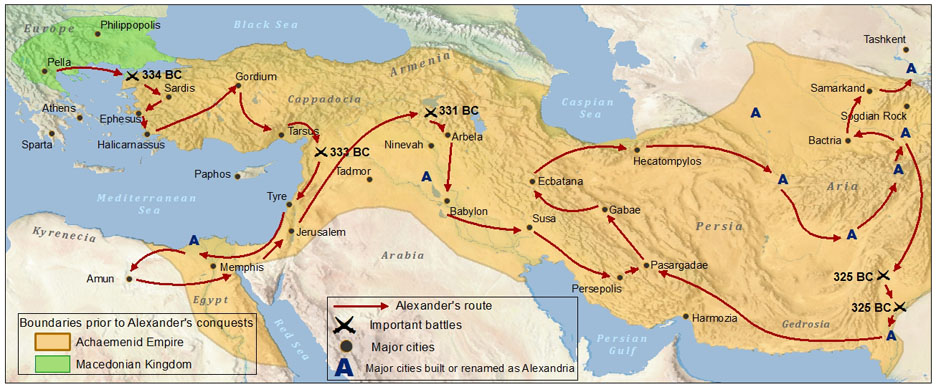

In 334 BCE Alexander crossed the Hellespont, joining with a vanguard that had crossed earlier, bringing the army's total strength to about 40,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry.

The Persian commander Memnon, a Greek mercenary, met him at the river Granicus, using the water as a tactical barrier.

But at the start of the battle Alexander immediately launched a frontal assault, catching the enemy by surprise and breaking through their lines.

Follow-up attacks by other units managed to disintegrate the Persian battle line and caused a general rout,

before the Greek mercenary hoplite core of the Persians had had the chance of participating in earnest.

Alexander proceeded southwards and was forced to reduce Miletus and Halicarnassus in sieges.

Especially the latter was costly in lives on both sides.

There was a clear strategic motivation for conquering the western and southern coastline of Asia Minor.

The Macedonians had no large fleet and were vulnerable to Phoenician and Egyptian ships.

The solution was to seize one harbor after another, denying those ships places to anchor.

In 333 BCE the Macedonian army marched through Cilicia into Syria, which was a tactical mistake, yet without dire consequences.

Darius III, great king of Persia, now came to meet his enemy personally in battle.

The Persians bypassed Alexander and cut his lines of supply and communications.

He was forced to reverse course and meet them at the Battle of Issus.

Darius's forces used the advantage of high ground, again behind a river, knowing that time was on their side.

Again Alexander sought the confrontation and broke through.

At that point the Persians could still have won, but Darius thought that the battle was lost and fled, prompting their collapse.

The great king later offered Alexander the western half of his empire in return for peace, but he disdained that, knowing that it effectively already was his.

After the battle, Alexander resumed his strategy of taking harbors.

At Tyre and Gaza he again had to conduct sieges.

The former, situated on a peninsula, proved very difficult to reduce, taking 7 months.

Afterwards Alexander had the population massacred for their stubborn resistance.

Once the resistance in the Levant was broken, Egypt, tired of Persian rule, happily surrendered without a fight, hailing Alexander as the new pharaoh.

The young king lingered a bit, making a personal pilgrimage to the oracle of the Siwa oasis.

This episode is shrouded in mystery; it is unclear what he asked the oracle and what it answered.

In 331 BCE he resumed his march, swinging back east, right into Mesopotamia, the agricultural heart of the Persian empire.

Darius had used the vast resources of his empire to gather a fresh army and met the Macedonians in the third large battle of the war,

at Gaugamela.

The Persian army was twice the size of the Macedonian and should have been able to outflank them,

but Alexander made his formation asymmetrical, partly neutralizing that advantage.

He managed to deliver his usual heavy cavalry charge with the usual devastating effect.

Darius saw his lines break and fled once more, but the Macedonians had to fight for hours to secure a final victory.

Gaugamela was decisive.

Darius fled and was pursued by Alexander, who stormed the pass of the Persian Gates and then sacked the Persian capital Persepolis.

Darius was taken prisoner by his satrap and kinsman Bessus, who had him assassinated and claimed the throne of the empire.

Bessus himself was betrayed by Spitamenes.

Of course Alexander would have none of the deeds of these upstarts.

In 330 BCE he set his army on the march again into the eastern half of the Persian empire: Bactria, Sogdiana and beyond.

The battles on this campaign were smaller, but far greater in number and taxed the army much more.

In 327 BCE, ever anxious for more glory, he led his army into what is now Pakistan and western India.

He beat the Indian king Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes river in 326 BCE and scored several other victories.

But the tide started to turn against him.

At the siege of Multan he was seriously wounded and could no longer lead the army from the front as he was used to do.

Exhausted by years of campaigning, the army revolted and forced him to turn back.

The fleet sailed along the coast while the army marched through the Gedrosian desert.

It was the terrain that inflicted Alexander's greatest defeat, with many men dying from thirst and hunger.

The army was back at Susa in 324 BCE.

In his absence many governors had misbehaved.

Alexander responded by executing several of them and setting things back into order.

He was planning new conquests in Africa, when in 323 BCE he suddenly fell ill and died.

After his death, without an heir, his senior generals, the Diadochi, took command.

They quickly fell out with each other and the empire was soon divided into several states:

the realm of Antigonos in the west, the Seleucid empire and Ptolemaic Egypt.

These kept fighting among each other and eventually succumbed to the Romans from the west

and the Parthians in the east.

Despite the short-livedness of the military and political gains, Greek culture was spread over southwest Asia and had a more lasting influence.

War Matrix - Conquest of Persia

Greek Era 330 BCE - 200 BCE, Wars and campaigns